KATA IN KARATE-DO

Karate training as a whole can be thought of as having three major components – kihon (basics), kumite (sparing) and kata (training forms) – and whilst each may be trained separately, they are really quite interdependent. An analogy may be the fingers and thumb of a human hand. Each finger may have a certain function – the index finger is useful for pointing directions and pressing buttons, another finger may be ideal for playing a musical instrument whilst the opposable thumb assists greatly in gripping. All digits can work independently but together they form an extremely functional and powerful tool.

Karate training as a whole can be thought of as having three major components – kihon (basics), kumite (sparing) and kata (training forms) – and whilst each may be trained separately, they are really quite interdependent. An analogy may be the fingers and thumb of a human hand. Each finger may have a certain function – the index finger is useful for pointing directions and pressing buttons, another finger may be ideal for playing a musical instrument whilst the opposable thumb assists greatly in gripping. All digits can work independently but together they form an extremely functional and powerful tool.

In any karate dojo a beginner student would be introduced to “kata” and an instructor, or senior student, may explain kata training to the beginner as “a series of karate techniques performed the same way each time in a predetermined pattern” and whilst this is not wrong, and is probably explanation enough for a new student, it’s a simplistic way of describing an important part of karate-do training.

Kata training is unique to Asian martial arts and as such has no real equivalent in Western arts or sports. Kata training is introduced to a beginner student only after they have attained a rudimentary understanding of karate basics (kihon). Kata training is introduced to ‘solidify’ these basic techniques and to extend them further to combinations of basics. It’s a foundation that teaches the body stances, movement and the principles of using arms, legs, hands and feet in a prescribed way. Kata is not simply a shallow mix of techniques performed rote style but rather an austere form of training that also teaches breathing, rhythm, fighting spirit and harmony of movement of the entire body.

Kata origins

Kata origins

If we consider the origins of karate from India to China through to Okinawa and Japan and then to the Western world, we need to keep in mind the flow of knowledge and the span of time. Hundreds of years ago there was no internet, there were no monthly karate magazines nor were there even any photographs . . . the flow and recording of information was not how it is today. As well, there were periods when the actual practice of martial arts was forbidden (for 300 years in Okinawa) and so the handing down of knowledge was very limited. In these times kata was the heart of Eastern fighting systems and was in fact the record of those systems and was one of the only ways the art was passed down from generation to generation. Kata was the ‘text book’ of a particular fighting system. A brief time line of karate development would look like this:

1377 – The King of Okinawa has an allegiance with the Chinese that leads to a cultural exchange between the two countries. This exchange was influential in the development of the Okinawan martial art Okinawa-Te.

1477 – King of Okinawa banned the ownership of weapons.

1609 – Japan orders the Satsuma clan to invade Okinawa which they did. The ban on weapons was continued and was extended further to eradicate the practice of the Okinawan fighting system. These actions resulted in the practice of these martial arts to only be done in secret.

1867 – Tokugawa Shogunate in Japan comes to an end and Okinawans now start to practice martial arts less secretively.

1901 – An influential group of martial artists led by Anko Itosu (mentor and instructor of Funakoshi Gichin Sensei) campaigned successfully to have karate taught in the curriculum of Okinawan schools. Funakoshi Sensei later spread this karate to Japan.

The karate taught in Okinawan schools at this time comprised mainly of kata and in fact it was a ‘watered down’ version as Master Itosu considered some of the more lethal techniques of the art were not appropriate to be taught to school children. These modifications allowed children to gain such benefits as improved health and discipline from karate without giving them the knowledge of the highly effective and more dangerous fighting techniques that the original kata contained.

The kata we practice today is a synthesis of techniques and concepts passed down over hundreds of years. Kata teachings were a closely guarded secret only taught to the most trusted individuals and although the kata may not contain all the original intent, they gave, and still give, great benefit to karate practitioners and led to the development of modern day karate-do.

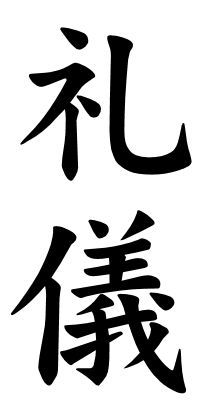

The Japanese kanji for “Reigi”

Elements of kata

Kata training should not be considered a mechanical execution of techniques performed to a certain embusan (floor plan or performance line) and useful only to complete a training session, pass an examination or win a competition. Rather karate kata should be thought of as having a life of its own and should be trained thus.

The first and last movement of every kata is a bow (rei) or more specifically, a standing bow (ritsu rei). This is an important point that perhaps needs to be drawn out further as it pertains to our all round karate training. “Rei” is a component of the Japanese word reigi that translates to mean respect, courtesy or good manners or simply put. . . etiquette. The subject of reigi is something that can be expanded upon in great detail and one that is perhaps hard to grasp for the Western mind. Suffice to say that without reigi, our karate becomes just another physical activity but lacking the character and depth that is a true hallmark of a martial art.

The first and last movement of every kata is a bow (rei) or more specifically, a standing bow (ritsu rei). This is an important point that perhaps needs to be drawn out further as it pertains to our all round karate training. “Rei” is a component of the Japanese word reigi that translates to mean respect, courtesy or good manners or simply put. . . etiquette. The subject of reigi is something that can be expanded upon in great detail and one that is perhaps hard to grasp for the Western mind. Suffice to say that without reigi, our karate becomes just another physical activity but lacking the character and depth that is a true hallmark of a martial art.

Etiquette will develop discipline in a martial artist although this may be difficult for a beginning student to understand. From this discipline structure will evolve and through this structure a better understanding of the concepts being taught will follow. “Karate will help you achieve self discipline” is a phrase often glibly spouted by martial arts marketers without too much thought however at a deeper level, over time, the benefits of reigi in one’s karate will flow through to everyday life and this can be particularly useful for young children.

The performance of kata relies upon many elements such as power, speed and correct technique to name a few, but having a calm and clear mind and strict concentration as well as maintaining one’s ‘ki’ (energy) is also vitally important. From the beginning to the end, the movements in kata should be liquid and flowing . . . even beautiful and rhythmic, with specified emphasis points (kiai or shouting points) showing great control and strength.

There are three other essential points that needed to be considered with kata:

1. Light and heavy application of strength

2. Expansion and contraction of the body

3. Fast and slow movements in techniques

There is no point using strength indiscriminately and speed itself may have little purpose but the combination of the above three points gives great meaning and depth to the performance of a kata.

Bunkai

The Japanese word “bunkai” means analysis or disassembly and is a term used to describe the fighting technique inherent in a particular movement of a kata.

As mentioned previously, kata was a way of passing down knowledge of a particular school of karate. Kata was meant to be studied solo (without a partner) and in doing so one could practice various self defence techniques against an imaginary attacker. The problem arises when a number of bunkai, or bunkai that could be considered fanciful at best, are attributed to a kata movement possibly because the passing of time has ‘eroded’ the original meaning, or possibly because of a lack of understanding.

But to back up a little, why is bunkai such a useful and necessary part of kata? Repetitive training of a kata is a vital part of all our karate training – particularly kata – but executing a technique a hundred or a thousand times without knowing the actual application of that technique gives the student no depth of knowledge of the art. Seeing the application and meaning of a particular kata technique can also aid in the execution of that technique. So by analysing, explaining and demonstrating a kata technique, an instructor can get across the true meaning of that element of a particular kata and this is the importance of bunkai in the study of kata.

But who says the bunkai for a movement in a kata is valid? To answer this, one needs to go back to the understanding that kata were designed hundreds of years ago and the originators embedded movements in their kata that simulated actual combat situations. Some of these combat situations may seem archaic to us now, for example in the kata Bassai Sho we perform ‘bo uke’ – a block against a staff attack. Nowadays, in our urbanised lifestyle, it would be unusual to be attacked by someone wielding a long wooden staff but in feudal times carrying such an implement was not uncommon so designing a technique to counter such a weapon was quite logical at that time.

In Shotokan karate – and in fact in all mainstream schools of karate – we try to adhere to the original bunkai concepts as designed by earlier masters. Some movements are self explanatory (lower gedan barai countering a front kick for example) whilst others can be more complex and require good research and / or good instruction from experienced and knowledgeable teachers. Unfortunately lazy, or insecure, instructors will sometimes make up a bunkai application in a kata rather than say they don’t know and this explanation may be diametrically opposed to the true meaning of that movement in the kata.

Generally bunkai – the true bunkai – for a particular kata will have one or maybe two versions not multiple ones. Bunkai should be considered the heart of karate and should not be tampered with like a plaything.

Oyo

Oyo

An extension of bunkai, and a very useful one, is called “oyo’ which roughly translates to application and is the part of kata training that allows an instructor and student to have more flexibility in teaching and learning.

Whilst bunkai is generally specific for a particular kata move (and is not up for interpretation), oyo training allows us to put our own interpretation (or interpretations) on the application of a particular move. Bunkai allows us analysis of a kata move whilst oyo is a practical application for actual self-defence. Oyo is what makes every kata a lifelong challenge to master! The only caveat with oyo training is that technique employed has its roots anchored in good karate technique and is not nonsensical or something out of a Hollywood movie!

In conclusion, there are many facets to our kata training and each needs to be practised to achieve the true essence of what kata personifies. Just going through the movements of a kata in a training session won’t give a student any major benefit and kata can give us so much in our karate life if studied correctly.